Race and the Whitewashing of History in our Textbooks

Note: this article contains some graphic images.

Most people in the United States don’t know the true history of the United States.

And this is on purpose.

As a history teacher, I can tell you that our textbooks are not designed to teach history. No, let me rephrase that: our textbooks are not designed to teach our true history. Textbooks are written by companies to sell at a profit. So textbook companies are really careful about what they put into textbooks because they want to sell a whole lot of textbooks to Texas, for example. The Texas State Board of Education chooses the textbooks that will be used by every student in the state. Therefore, textbook companies make the books palatable to Texas in order to sell as many books as possible.

Even if you have never lived in Texas, you know about the Alamo. Ever wonder why the Alamo gets a whole lot of patriotic treatment? Thank Texas.

Most Americans look on the Alamo as a moment of pride in American history. These brave Americans were standing up to tyranny, after all. Right?

Wrong. These Texans were at war with Mexico trying to win independence because Mexico had the gall to tell them that they can’t have slaves.* That’s right: the Texas Revolution, in part, was about the preservation of slavery.

And those guys at the Alamo? They were told that it was foolish to stay there and that they were going to die. They stayed anyway. And you know how it ended: they all died. Well, not everybody, actually. There were 5 dozen survivors: women and children, Tejano soldiers, and slaves.

Santa Anna freed those slaves.

However, you wouldn’t get that from the textbook:

It is America’s history regarding race that is egregiously absent from American history textbooks, however. And, again, this is purposeful. Textbook companies purposely avoid controversy so that they can sell textbooks. And what is more controversial than race in American history?

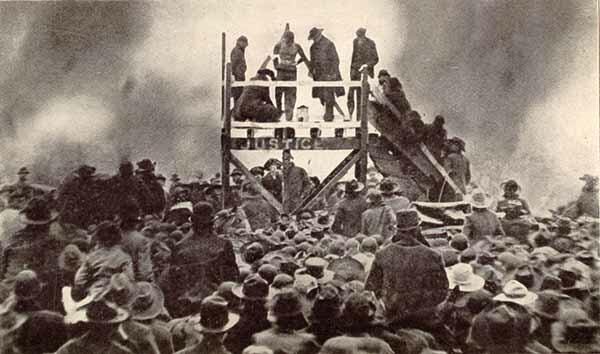

For the last 20 years, I have been giving presentations about race and lynching to high school students. Although the presentation has changed over the last two decades, I always show them this graphic:

Nothing is more whitewashed in American history textbooks — both literally and figuratively — than our history regarding lynching.

That section displayed above is typical in textbooks:

1) It confines lynching to a short time frame, although it has been a part of our history before 1882 and after 1892. In fact, last month the world watched as George Floyd was lynched. Yes, that was a lynching by definition.

2) It minimalizes the death toll to 1,400. The actual number of lynching is not known as they were not officially tracked.** But it is certainly well over 1400. Actual estimates put that number to 16,000 on the conservative side and upwards of 60,000 on the other end. And it leaves out the fact that although African Americans make up over ¾ of those lynched, there were organized lynchings of Latinos in the Southwest and Chinese in the Northwest, too.

3) It provides a sanitized definition of what lynching was in American history. Lynchings were more than just isolated incidents when African Americans were “shot, burned or hanged without trial in the South.” First of all, lynchings occurred everywhere, not just in the South. Secondly, and most importantly, lynchings were treated as entertainment in many cases to white crowds, and used as terrorism in all cases to black populations. They were aided and abetted by law enforcement and city leaders. They were planned spectacles advertised in newspapers. Railroads gave special rates so people could attend. Families would go to lynchings, complete with picnic lunches. Children were encouraged to participate. Souvenirs were made from the charred remains of human beings that were sold among crowds for pennies. Body parts would be displayed in public places as a warning to black people living in the town that this can happen to them as well if they do not follow the rules.

In short, lynching was and is a form of white supremacist terrorism.

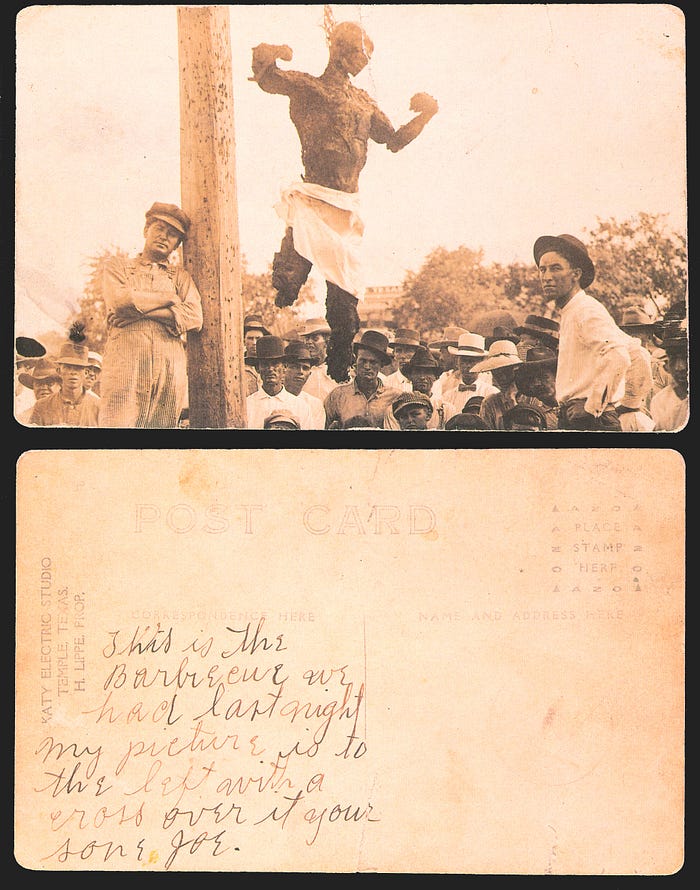

You won’t find many lynching photographs in textbooks either (if at all), although these photographs were extremely common. The existence of hundreds of these photographs today, complete with people posing with the bodies is not only incredibly disturbing to view but also a sign of the casual nature these events were to those who participated in the violence. After all, a majority of Americans in the late 1800s believed that lynchings were justified depending on the situation.

You won’t read the stories of victims, such as Mary Turner. Mary Turner was eight months pregnant when she was lynched in Georgia in May of 1918. She was strung upside down from the branch of a tree, her clothes burned from her body. Her unborn baby was cut from her abdomen before she was riddled with bullets. The sign that marks the spot today is often vandalized and destroyed, because apparently people don’t like to be confronted by the truth of history.

You won’t read the story of Henry Smith who was lynched in front of a crowd of thousands.

Or, Jesse Washington, either. He was seventeen years old when he was lynched in Waco, Texas. His fingers were slowly cut off one by one and thrown to the crowd, who scrambled after them like they were gold. His lynched body was photographed and made into postcards that were sent through the U.S. mail.

You won’t find a reference to the “Scottsboro Boys” in most textbooks, either. This incident was the all-too-common practice of false accusations against people of color for committing crimes against white women. In Scottsboro, Alabama, nine black teenagers were falsely accused of rape and the impending trials and appeals uncovered the severe inequities in our legal system. But even so, this incident was not isolated. Decades later the Central Park Five experienced the same treatment despite any evidence of guilt. This event is significant because the racial undertones of the case were amplified by the person who is now president of the United States. At the time, he put out full-page ads advocating the death penalty for these young men.

When race issues spurred violence in American history, they were often described as “Race Riots.” The term “riot” is purposefully used here to divert from the true nature of these events, which always resulted in the mass killing of black people or brown people. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921, for example, white mobs ransacked one of the most prosperous black neighborhoods in the country known as “Black Wall Street.” They looted businesses, burned homes and massacred hundreds. In my 30 years of teaching, I have never used a textbook that mentioned this incident in a general survey American history course.

And when incidents are mentioned, they are written in such a way as to pass blame or distort reality; often, by leaving out context:

In Chicago in 1919, a young black boy drowned after being struck with rocks by white people on the beach, upset that he accidentally swam into the white section of Lake Michigan. This touched off days of unrest. This is all that is said of that incident in The Americans, although incidents like this were occurring all over the country at the time:

The Civil Rights Movement is also whitewashed. Although Emmett Till is sometimes mentioned in passing depending on the textbook (no textbook that I used in 30 years even had Emmett Till in it, except AP versions), there are no serious discussions in textbooks about the trial that occurred in which the men, who would later admit to the killing, were found not guilty in a 67-minute deliberation that would have been a lot shorter had not the jurors stopped to indulge in some soft drinks provided to them by the court. Trials such as this were not isolated to just Emmett Till, but are woven into the fabric of the American judicial system. These inequities are still there in plain sight. Look at the case of Curtis Flowers, for example.

Although usually there is an entire chapter devoted to the Civil Rights Movement in American textbooks, the complexities of the movement are absent. Martin Luther King, Jr. is almost universally lionized and Malcolm X is looked at with suspicion. Interestingly, as the movement progressed Martin Luther King, Jr. arguably became more radical, honing his message on poverty, housing and labor. When he was murdered, he was in Memphis supporting the mostly black striking garbage workers and was not favorably viewed by most Americans at that time. On the other hand, Malcolm X broke with the Nation of Islam and struck a more conciliatory tone in regard to race and action prior to his assassination. You won’t find a serious discussion about the fluidity of the movement or its leaders in textbooks.

In American history textbooks, the Black Power Movement is not accurately represented, nor is the Black Panther Party. Absent altogether is the organized campaign of the American government to infiltrate and discredit not just the movement but the leaders as well. The social unrest that we are experiencing now is not unlike the social unrest that occurred throughout the sixties, which was often precipitated by instances of police brutality. But you wouldn’t know that after reading an American history textbook.

Furthermore, American History textbooks act as if the Civil Rights Movement ended and was a success. And that’s the problem right there: the belief that issues are “past” and were solved some time ago makes the resurfacing of issues that have been with us since the beginning all the more difficult to understand and process.

Make no mistake: the present situation in America is not new. It is built on hundreds of years of inequality and misrepresentation. Leaving discussions about this out of textbooks and American classrooms are egregious errors. History gives us context to the present only if that history is complete with all of its blemishes and controversies.

When we don’t understand our history, we have the tendency in the present to clutch our pearls and claim, “I can’t believe this is happening!”

When, in actuality, it has been happening for a long, long time.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — —

*In order to promote immigration to Texas, Mexico opened the border to Americans on two conditions: No slavery and they had to accept Catholicism. Although American immigrants agreed to those terms, they didn’t adhere to them. Finally, Mexico got fed up with the blatant violation of their laws and closed the border. They didn’t want more Americans coming into Texas anymore. That’s when the Texas Revolution occurred.

**When people were lynched, the death certificates did not indicate lynching. Instead, the phrase “died at the hands of persons unknown” was often used, and became a morbid euphemism for lynching.

— — —

For more information:

More information about lynching photography can be found in Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America by James Allen. There is also a website based on this book.

At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America by Philip Dray is a good start to understand the history of lynching in America.

A thread posted on Twitter in 2019 by writer Michael Harriot from The Root highlights the lack of attention made to issues in history, in particular the wars fought against the KKK. This is well worth a read and is another great example of how aspects of our history are deliberately hidden.

The New York Times did an extensive study of American history textbooks, highlighting how politics often shape how history is presented. This is eye-opening to anyone interested in how the American education system is shaped by politics and money.

The podcast In the Dark devoted its second season to the Curtis Flowers case and is worth a listen.